Literature Review Mindfulness Interventions With Youth Learning Disabilities

Abstract

Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs) hold hope for building resilience in children/youth. We were interested in understanding why some MBIs comprise arts-based methods, and what key findings were identified from the study of these MBIs. We used a scoping review to address our research questions. Scoping reviews tin help united states better sympathise how unlike types of evidence can inform practice, policy, and research. Steps include identifying research questions and relevant studies, selecting studies for analysis, charting data, and summarizing results. Nosotros identified 27 research articles for assay. MBIs included the apply of drawing, painting, sculpting, drama, music, poetry, and karate. Rationales included both the characteristics of children/youth, and the benefits of the methods. Arts-based MBIs may exist more relevant and engaging particularly for youth with serious challenges. Specific focus should exist paid to ameliorate agreement the development and benefits of these MBIs.

Mindfulness is a holistic philosophy and mode of being in the world, and it tin can be both a state (an feel) and a trait (a personality characteristic or disposition) (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs) can aid people learn to focus their attention, and with regular practice, they can learn to exist aware of their present thoughts, feelings, and actual sensations without negative judgements (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). With this nonjudgmental awareness, an individual can develop the ability to choose a response to sorry situations and emotions instead of reacting with unhealthy behaviors and interpretations (Horesh & Gordon, 2018). Indeed, emotion regulation is an important component in treating a variety of circuitous mental wellness challenges including feet (Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009). Every bit a style of being in the earth, mindfulness represents an inner-resource that contributes to resilience, which is the ability to recover from tumultuous circumstances (Bajaj & Pande, 2016). Thus, youth facing a variety of psychosocial stressors may find mindfulness a helpful strategy for mitigating challenges and building resilience.

MBIs take been developed for a range of weather in both clinical and good for you adult populations. Well established MBIs include Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, 1990), Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002), and Credence and Commitment Therapy (Human activity) (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). At that place is prove that MBSR improves mental health and reduces symptoms of stress, feet and depression, and MBCT prevents depressive relapse (Fjorback, Arendt, Ornbol, Fink, & Walach, 2011). MBIs have also been found to exist helpful in reducing symptoms of anxiety (Vollestad, Birkeland Nielsen, & Hostmark Nielsen, 2012). Act combines mindfulness and cognitive therapy with an emphasis on treating anxiety and depression but is typically delivered in a traditional one-on-one counselling setting. Most other MBIs are facilitated via group delivery making them cost-effective, and providing the additional do good of developing social competencies (Klatt, Buckworth, & Malarkey, 2009).

A wide multifariousness of MBIs, oft adapted from programs developed for adults, have as well been investigated for utilise with children and youth in clinical settings and in schools with promising results. Information technology appears that MBIs in schools may improve resilience (Zenner, Herrnleben-Kurz, & Walach, 2014). Others take constitute that youth with serious mental wellness challenges who participated in MBSR adult improved attending and mood, self-concept, and interpersonal relationships (Van Vliet et al., 2017). A review of the evidence for MBCT for improving self-regulation in teenagers indicated that youths reported better self-regulation and coping (Perry-Parrish, Copeland-Linder, Webb, Shields, & Sibinga, 2016). Similarly, a review of MBIs for youth with feet reported that MBIs are effective for the treatment of anxiety disorders in youth (Borquist-Conlon, Maynard, Esposito Brendel, & Farina, 2017).

Tan and Martin (2013) summarized the mechanisms that are thought to contribute to the effectiveness of practicing mindfulness. These include improved attentional capacity, which is important in learning processes; increased self-awareness and the power to notice thoughts as transitory experiences that are not necessarily truthful (flexible thinking); and reduced distress and/or distress tolerance through the process of accepting thoughts and feelings rather than repressing or trying to command them. These mechanisms of modify and consequent benefits tin build on each other. For example, with improved attention and focus, self-awareness tin exist developed then that a youth tin understand and express their feelings. With improved emotion regulation, they can cope better with challenges, which can bear on overall mood and self-esteem (Coholic et al., 2019). However, this is a developing field and some take argued that findings should be considered tentatively promising (Zenner et al., 2014), while others argued that nosotros demand more than research that examines the mechanisms of change that participants experience and/or cocky-written report (Alsubaie et al., 2017; Chiesa, Fazia, Bernardinelli, & Morandi, 2017), that is, learning mindfulness may non exist the but factor implicated in change.

When MBIs are adapted from adult programs for use with children and youth, modifications are often made to make the programs more than relevant for immature people, for example, shortened meditation exercises and the addition of experiential activities, but typically, the structure of the programme adheres to the original adult program. Some researchers take argued that there is a need to better understand the factors contributing to changes in children's behaviours, feelings, and thoughts every bit a upshot of having participated in an MBI (Harnett & Dawe, 2012). In our own work, we have found that the enjoyment created through the use of arts-based methods engages our target population and is consistently reported equally one of the most favorite aspects of our arts-based MBI (Coholic & Eys, 2016). Thus, we were interested in better understanding what research exploring arts-based MBIs has been completed and why arts-based approaches were used by researchers and facilitators. With this information, future areas for enquiry and practice tin can be identified.

Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews have been successfully used to aid in the design of research, inform best policies/practices, and locate research gaps in the literature (Pham et al., 2014). Various definitions take been proposed to describe scoping reviews including to identify key concepts and sources of available evidence (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005); to synthesize and analyze diverse research and not-research fabric (Davis, Drey, & Gould, 2009); and to map the literature on a specific topic and then that we can meliorate understand how unlike types of show can inform practise, policy making, and research (Pham et al., 2014). Scoping reviews are about commonly used to apace develop a description and analysis of bachelor literature in a specific area (Grant & Booth, 2009). Study quality is not assessed, thus, more than studies tend to exist included compared to systematic reviews/meta-analyses. Therefore, the scoping review was selected every bit a methodology well suited to quickly, and with limited resources, map the emerging literature with regards to the utilise of arts-based grouping MBIs with children and youth. In a scoping review of scoping reviews, Pham et al. (2014) indicated that Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) framework was the most common methodological framework employed. We also used their five-stage framework to guide our work with the following steps: (1) identifying inquiry questions, (ii) identifying relevant studies, (three) written report selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating and summarizing. Consultation is listed as an optional component (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005).

Method

Research Questions

We were interested in exploring the existent research pertaining to arts-based grouping MBIs with children and youth aged 8–18 years old. The research questions were: (1) What are the MBIs that primarily utilize arts-based methods to facilitate mindfulness with children and youth? (2) Why do these MBIs focus on using arts-based methods? and (3) What are the key findings from these programs?

Selection Criteria

We focused on inquiry published from 2000–2017 because studying MBIs with children and youth is an emergent area of enquiry, and beginning with the yr 2000 ensured a comprehensive search. Literature published in English was the focus as we did non take the resources to translate papers written in other languages. Criteria was too related to type of intervention including MBIs with children and youth anile 8–eighteen years onetime including all types of challenges and rationales for participation in the MBI; grouping commitment; and whatsoever group size and mix of genders. Chiefly, for the purposes of our review, the MBI had to take a major focus on arts-based methods. Nosotros understood arts-based methods to include a variety of artistic and experiential approaches such equally cartoon, painting, sculpting, games, movement such as karate or tai chi, drama, music, and verse/journaling. We agreed that the MBIs had to be primarily focused effectually teaching mindfulness-based practices and concepts by style of arts-based activities so that arts-based activities were facilitated in every session serving as the context for the delivery of the mindfulness-based practices. We included all cultures, practitioner-types, and geographical/concrete locations.

Identifying Relevant Studies

As academic journals are increasingly spider web-based we decided to conserve our limited resources past solely searching electronic databases. Our search was limited to English articles published between January 2000 and March 2017. To identify relevant studies a number of search terms were selected in consultation with one of our university's librarians and based on the research questions. For instance, an article's abstract or title would require the term mindfulness and synonyms for children/youth, groups, and arts-based/creative interventions. These terms were separated by Boolean operator 'AND,' whilst synonyms were separated by 'OR.' Terms with varying suffixes were truncated with the asterisk symbol to yield more studies. The terms were then used to search the abstracts and titles of manufactures in their respective databases (meet Tabular array ane for listing of keyword search terms). The 2d and third authors, who were senior social work students preparation in the offset author'southward enquiry program, independently searched 22 databases which were expected to yield the most relevant results using the same set of search terms (see Table two for a list of the databases searched).

Study Choice

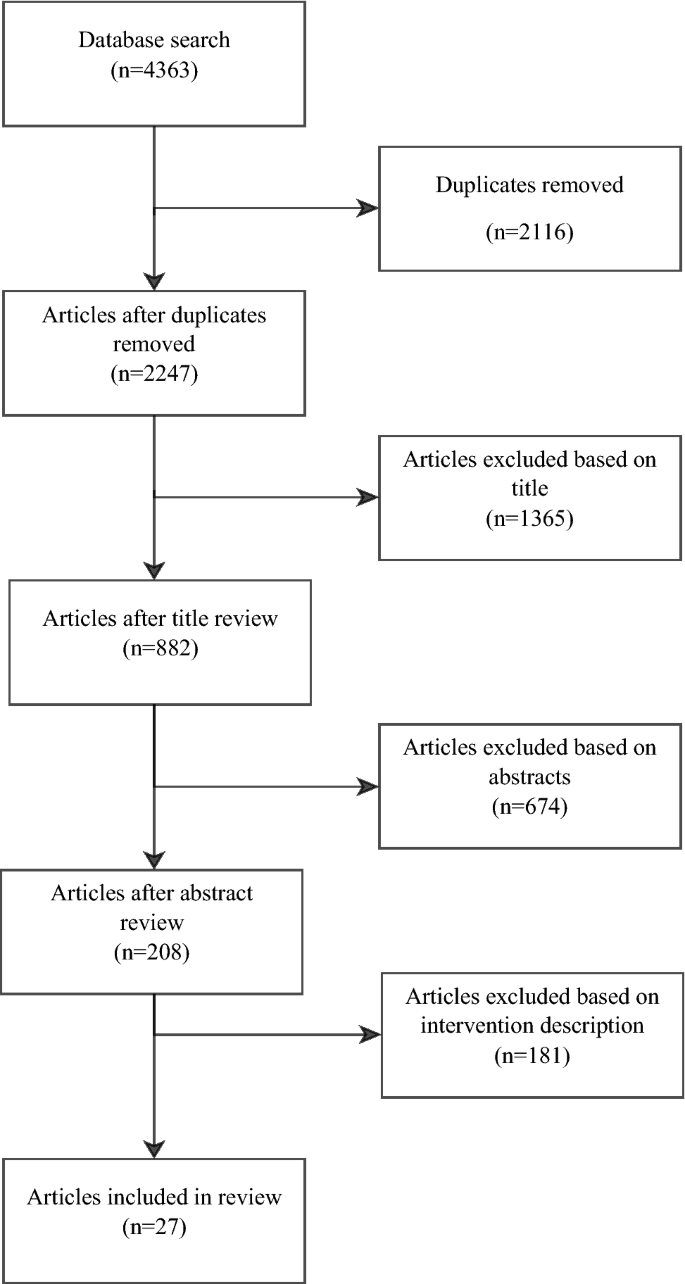

The initial search yielded 4363 manufactures. This number was reduced when 2116 duplicates were removed. The second and third authors then independently reviewed the titles and abstracts to identify articles that did not see the inclusion criteria; this eliminated an additional 1365 articles. Some other 674 articles were eliminated post-obit the abstract review leaving 208 articles. The description of interventions in the remaining manufactures were then independently reviewed by the second and third authors to assess whether the interventions met the inclusion criteria. When there was a lack of consensus between these two authors, discussions were held with the first writer regarding the inclusion of an article in order to resolve the discrepancies. The period chart in Fig. 1 depicts the process of searching and screening the manufactures. Additionally, we institute that our search yielded several dissertations merely they were eliminated during the intervention description review due to time and resource constraints. Ultimately, 27 studies were selected for inclusion and analysis.

Article search flowchart

Charting the Data

The 2nd and third authors charted the 27 articles according to the following extraction fields: publication year, authors, championship, country, purpose/research questions, population characteristics, sample size, study blueprint, intervention elapsing and description, facilitator qualifications, comparator description, effect measures, outcomes, and researchers' rationales for the use of arts-based MBIs (see Table iii for a listing of included manufactures and relevant extraction data).

Results

The analysis phase of a scoping review should include three steps: analyzing the data, reporting results, and applying significant to the results. Analysis typically involves a descriptive numerical summary and a thematic analysis (Levac, Colquhoun, & O'Brien, 2010).

Characteristics of Arts-Based MBIs

Of the 27 studies, 10 were based in Canada, 8 were based in the Usa, and five were based in Commonwealth of australia. Ane study was from South Korea, Norway, and Kosovo respectively. Ane article reported on two studies, one from Australia and another from Sweden evaluating the aforementioned MBI. Studies included children/youth between the ages of seven–27 years, with the highest minimum age requirement being xvi years. Twenty-1 of the MBIs were offered to boys and girls. Most of the studies targeted specific populations that included youth with chronic pain and affliction, low income, placement in foster care, incarceration, learning disabilities, anxiety, eating disorders, postal service-traumatic stress disorder, depression, disruptive behaviors, and other mental health challenges. Six studies recruited youth from schools or the general population.

Eight studies employed solely qualitative designs. Nine of the remaining studies had primarily quantitative designs whilst also featuring qualitative methods. Six studies identified themselves equally randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compared to 14 intervention trials that were non-RCTs. Eight of the non-RCT designs included control groups. Twenty-three of the studies had total sample sizes of less than 100, merely one RCT included 347 participants. New programs usually require preliminary evidence of benefits earlier being studied more widely. Thus, many of the studies were pilot projects (Jee et al., 2015), feasibility studies (Klatt, Harpster, Browne, White, & Instance-Smith, 2013) or exploratory studies (Milligan, Badali, & Spiroiu, 2015). Enquiry investigating arts-based MBIs is emergent, which may business relationship in part for the heterogeneity of the MBIs and the study designs.

Integra Mindfulness Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) (Milligan et al., 2015, 2016), Taming the Boyish Mind (Tan & Martin, 2013, 2015), and the Holistic Arts-Based Program (Coholic & Eys, 2016; Coholic, Eys, & Lougheed, 2012) were the only MBIs reported in multiple studies. Briefly, MMA aims to decrease challenging behaviors, increase cocky-sensation, control, and adaptability, and improve social and self-defence skills. The 20-week program consists of weekly 1.5-h sessions that include mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mixed martial arts. Key mindfulness concepts emphasized are impermanence, nonjudgment, acceptance, letting go, and focusing on the moment (Haydicky, Wiener, Badali, Milligan, & Ducharme, 2012). Taming the Adolescent Mind (Tan & Martin, 2013) is based on the adult MBSR only delivered over 5-weeks in 1-h group sessions. Modifications to the developed MBSR include shorter meditations and a variety of activities such as mindful drawing, eating, listening to music, and sculpting given youths' demand for movement and familiar activities. Program goals include mastering attending regulation, improving internal and external awareness, nonjudgmental credence, and learning how to be mindful. Finally, the Holistic Arts-Based Program (HAP) is a strengths-based group intervention with the following goals: teaching mindfulness in accessible and relevant ways; improving self-sensation and expression of feelings and thoughts; developing self-compassion and empathy; and recognizing and shoring upwards strengths. Information technology was developed and refined through research with marginalized children and youth, and is traditionally offered over 12 weeks in weekly ii-h sessions (Coholic & Eys, 2016).

Rationales for an Arts-Based Arroyo

While the rationales for the utilise of arts-based methods were not ever well articulated, some rationales were continued with characteristics of the participants including that activities had to be age advisable, and the need to engage young people who can be noncompliant, accept short attention capacities and a diverseness of interests, possess express verbal fluency, and struggle with abstract reasoning. Himelstein, Hastings, Shapiro, and Heery (2012) noted the power of their MBI to appoint and retain incarcerated adolescents who are a particularly difficult group to appoint in helping processes. Also, Coholic (2011) argued that some marginalized youth may not have the capacities for, or interests in, learning mindfulness past mode of traditional practices such as sitting meditations. Another study noted that immature people reported a desire to play during MBIs (Diaz, Liehr, Curnan, Dark-brown, & Wall, 2012). Artistic methods involving play were adopted in Diaz et al.'s (2012) work to improve retention. Similarly, Tan and Martin (2013) noted that MBIs for youths should incorporate a range of activities that involve physical activity and pastimes already familiar to adolescents (drawing, listening to music, art, etc.). Yook, Kang, and Park (2017) reported physical action was utilized considering of its many benefits for psychological health in full general. Thus, mindfulness needs to be facilitated in a manner that engages youth in a strengths-based helping process that promotes success.

Other rationales were connected with the ability of arts-based methods to teach mindfulness-based practices and concepts including the processes of self-expression, improved understanding of feelings and thoughts, and cocky-pity and not-judgement. Arts-based methods included martial arts, tai chi, theatre/drama, drawing, sculpting, painting, music, creative writing and more. For example, Klassen (2017) stated that journaling could meliorate participants' self-awareness, and Milligan et al. (2016) commented that interventions utilizing motility can improve a youth's ability to observe and accept distressing sensations and emotions. In our ain MBI program, painting to different types of music helped participants to explore and express feelings and thoughts, and drawing oneself as a tree helped the participants to share about themselves and develop self-awareness (Coholic & Eys, 2016). Other experiential examples included Burckhardt, Manicavasagar, Batterham, Hadzi-Pavlovic, and Shand'southward (2017) use of theatre to help participants exercise idea improvidence, and Gordon, Staples, Blyta, Bytyqi, and Wilson'southward (2008) use of trip the light fantastic to reduce concrete tension and explore emotions. Artistic interventions were likewise used in a didactic manner such as when Ruskin et al. (2017) used finger traps to illustrate the concepts of credence and resistance. Meagher, Chessor, and Fogliati (2018) used a multi-sensory teaching aid to explain the transient nature of thoughts.

Key Findings from the Arts-Based MBIs

Diverse benefits were reported and included improved responses to stress and depressive symptoms (Livheim et al., 2015), increased comfort with challenging emotions (Burckhardt et al., 2017), and being able to recollect before acting and other metacognitive skills. For example, Haydicky et al. (2012) reported that boys with ADHD had meaning improvements in parent-rated oppositional defiant problems and comport problems. Improved self-concept (Coholic & Eys, 2016) and feelings of confidence and happiness (Yook et al., 2017) were noted equally were feelings of general well-beingness and interconnectedness (Wall, 2005).

Most of the studies were focused on specific populations and findings were related to the goals of the MBIs and characteristics of these populations. For instance, Atkinson and Wade's (2015) MBI was focused on the prevention of eating disorders. They ended that the MBI had a positive impact on weight and shape concerns, which are relevant in eating disorder prevention. They besides concluded that the girls in their study indicated a strong preference for the increased use of visual and interactive activities. Lagor, Williams, Lerner, and McClure (2013) found that their MBI reduced anxiety in chronically sick youth, and Ruskin et al. (2017) found that youth with chronic hurting reported learning mindfulness helped them to cope meliorate with their pain. Waltman, Hetrick, and Tasker (2012) studied adolescent males living in residential treatment with poor behavior command and noted that the largest self-reported modify was in the power to notice feelings without having to react to them, which is a skill peculiarly important for these youth. As well, there were improvements noted in trauma symptoms in youth diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Gordon et al., 2008).

Several of the studies found mixed or unexpected results. For case, 1 written report constitute participants' eye rates, a measure of physiological stress, increased following the intervention (Jee et al., 2015). This was attributed in part to the population's (traumatized youth-in-care) possible desensitization to stress, and the reality that practicing mindfulness can heighten sensation of difficult emotions. Tharaldsen (2012) explained that contradictory findings are valuable as they encourage re-examination of conceptual frameworks. They also pointed out that an increased awareness of difficult feelings could lead to participants feeling worse than at the beginning of an intervention. Thus, they ended that mixed methods inquiry is about helpful equally different types of data tin can help us understand research results in a more than thorough manner.

Consultation with Youth

An optional step in a scoping review is consultation with appropriate stakeholders (Levac et al., 2010). Nosotros decided to invite youth (aged 11–17 years) who had recently participated in HAP groups to take part in a group discussion regarding our preliminary findings from the scoping review. Given these youths' recent experiences in an arts-based mindfulness program, we thought it would be interesting to elicit their viewpoints regarding what we found in the literature regarding rationales for using arts-based methods. This also reflected our delivery to including youth in our inquiry processes in meaningful ways. Six youth from three dissimilar HAP groups attended an hour-long meeting where we provided pizza and an opportunity to appoint in some arts-based activities as incentives. At the beginning of the word, we asked the youth to think about their contempo experiences in HAP and to compare these with the following rationales for using arts-based methods in MBIs, which were written on a white board: (1) engaging and interesting, (2) promote the development of cocky-awareness, (three) help participants pay attention, (4) help participants to stay with uncomfortable feelings, (5) address retentiveness, (half-dozen) aid self-expression, and (7) address youth'due south need for movement. Through our group word, nosotros encouraged the youth to identify which of these vii rationales virtually resonated with them. They identified 3 factors that were well-nigh cogitating of their own experiences in HAP: (1) arts-based methods were engaging/interesting and "non ho-hum" (two) arts-based methods helped them pay attending and focus, and address their "wandering minds" and, (3) arts-based methods helped them limited themselves. They added that the arts-based methods were "fun and different" and that they have been able to carry on with some of the activities at abode. They also appreciated the arts-based approaches to breathing, which helped them learn how to focus on their jiff and meditate.

Give-and-take

This scoping review examined why and how arts-based methods were used in MBIs. A multifariousness of approaches were studied with diverse youth populations with a variety of challenges. Because arts-based MBIs were oft adult for a specific population, a skilful number of the studies were pilot projects investigating the suitability and benefits of the MBIs. Rationales for the use of arts-based methods included both the characteristics of children and youth, and benefits of the methods themselves. In our consultation with a minor group of youth, they confirmed that arts-based methods were engaging, interesting, fun, and helpful. Participating in the MBIs helped the youth develop capacities such as self-awareness and non-judgment, and abilities to cope with challenges such every bit poor mood and emotion regulation.

There are sound rationales for using arts-based methods based both on participant characteristics and the benefits of creative approaches. One of the main reasons identified for the use of arts-based approaches was the ability of these methods to engage difficult to attain youth and/or youth with challenging bug such as chronic pain or eating disorders. Thus, many of the creative MBIs were developed for specific youth populations including marginalized youth, youth with chronic pain, incarcerated youth, and youth with learning disabilities. The benefits reported in the studies indicated that mindfulness-based practices and concepts tin be taught by way of arts-based methods, and can take benefits for youth who may non engage in a more traditional MBI such as MBSR. When working with youth, it is important to enable them to engage with methods that they discover enjoyable, meaningful, and helpful for self-expression and learning. Nosotros should not diminish the importance of creativity, fun, and play for children and youth learning new skills and concepts.

In fact, arts-based group modalities have a long history within helping practices with children and youth (Kelly & Doherty, 2017). In item, they have been used extensively in non-deliberative social group piece of work practice. Non-deliberative practice recognizes that there are multiple avenues for self-expression that do not rely on verbalization. Instead, the arts and creative processes deed as analogs for situations and challenges that youths face outside of the group (Lang, 2016). Others take found that arts-based methods help people express their thoughts and feelings that would otherwise remain unidentified (Sinding, Warren, & Paton, 2014). Indeed, youths with communication challenges may detect arts-based modalities more accessible and feasible than the high level of verbalization and cognition required for more traditional talk-based interventions. Furthermore, group-based arts and crafts have been identified as a source of enjoyment for marginalized youth who live in unstable environments (Dial, 2002). Thus, they are highly engaging and tin become a refuge for children and youth. Moreover, they tin be culturally competent practices. For example, crafting has been recognized equally a holistic intervention appropriate for use with Ethnic peoples living in Canada (Archibald & Dewar, 2010).

Given the promising benefits of MBIs and arts-based interventions with youths, a combined approach may make more than sense particularly for children and youth dealing with serious issues. The practices may work synergistically, for instance, the art-making process provides children an in vivo opportunity to not only explore analogous situations but to additionally do mindful sensation and credence. Mindfulness is a complicated concept to teach didactically; it may crave experiential activities such as those found in arts-based social work groups (Thompson & Gauntlett-Gilbert, 2008). Arts also provide youths a unique method of practicing and embodying mindfulness that does not rely on sitting meditation. The frontal lobe of young people is generally in the process of developing and their executive functioning skills are limited (Greenberg, 2006). A lack of attention regulation may intensify the difficulty of sitting meditation specially for marginalized youths who are also dealing with challenging life situations. Creative arts-based meditation involving sound tracks and sculpting, actively engage multiple sensory inputs including visual, auditory, and tactile systems. Importantly, by engaging youths in enjoyable and successful activities, they can learn about and practice mindfulness-based practices and concepts.

Research Directions and Implications for Practitioners

Based on reported results and the needs/developmental stages of children and youth, practitioners and researchers should exist encouraged to facilitate and study MBIs that focus on arts-based approaches. The written report of arts-based MBIs is emergent, which may account in part for their lack of prominence in this field and the diverseness of approaches being developed and studied. We concur that there is a demand for MBIs that are youth-centered in their design and shaped past feedback from youth every bit opposed to adaptations predetermined to exist appropriate for use with immature people (Diaz et al., 2012). Too, authors writing virtually arts-based MBIs should more thoroughly describe the synthesis of exercise wisdom, research, and feedback used in the design and commitment of their MBI. Generating a sufficient evidence base is vital for the dissemination and report of MBIs. Thus, we encourage researchers and practitioners to draw on existent arts-based MBIs that testify promising benefits for children and youth rather than develop new programs.

It may be more circuitous and challenging to offer creative MBIs as researchers and facilitators crave grooming not just in mindfulness only in arts-based approaches every bit well. For instance, one could non facilitate the MMA program without having gained avant-garde belts in various forms of martial arts (Milligan et al., 2015). Yet, in that location are ways to accost the need for specific facilitator qualifications. As Haydicky et al. (2012) explained, volunteers with martial arts expertise and advanced students of MMA could assist qualified facilitators. Nosotros have previously encouraged helping practitioners without specialized degrees in creative therapies to offer arts-based methods as part of their practices because arts-based methods are used as tools for engagement and self-expression, and didactics concepts and practices (Coholic, Lougheed, & Cadell, 2009; Coholic, Lougheed, & LeBreton, 2009). Helping practitioners tin access the plethora of resources in arts-based approaches in guild to proceeds conviction in incorporating these practices into their interventions (Carey, 2006; Malchiodi, 2007).

In line with other researchers, we have found that feedback from youth indicated that the arts-based nature of our MBI was a key component in their date and appreciation of the program (Coholic & Eys, 2016). Thus, learning and practicing mindfulness, in and of itself, is likely not the only mechanism of alter. It is quite possible that the effectiveness of a plan might exist due to a combination of factors including grouping work, mindfulness practice, and other factors such as specific cultural practices and/or an arts-based approach to learning mindfulness. As enquiry in this field develops, information technology might become more than evident that some arts-based methods work more effectively for specific issues or youth populations. For instance, we have often struggled with engaging male person youth over the age of fifteen years in HAP. Mayhap for these young men, learning mindfulness via movement such every bit karate or outdoor activities would be more highly-seasoned and relevant. In general, nosotros need to better empathise what methods work for whom, and all of the factors contributing to change every bit a upshot of having participated in an MBI.

Limitations

The literature in the surface area of arts-based MBIs with children and youth includes a broad diversity of programs of varying lengths facilitated with various groups of youth. In future reviews, researchers should focus on specific populations and challenges, which could develop our understanding of constructive approaches for particular groups of youth. This would also brand the review procedure more manageable and in-depth. For example, Simpson, Mercer, Simpson, Lawrence, and Wyke (2018) conducted a scoping review that explores MBIs for young offenders. Besides, we lacked the fourth dimension and resources to include a review of dissertations, which may exist where some novel approaches are first described and studied. We note that a scoping review is very time consuming and additional homo resources would take helped us finalize the results in a timely manner. Besides, in our review, it was sometimes challenging for us to empathise if an MBI could be considered arts-based, especially since many of these MBIs were not described with enough item. Thus, there is a chance that we eliminated some MBIs because the programme was not described in sufficient detail for us to appraise how arts-based approaches were used.

Finally, our consultation occurred with a small group of youth. Nosotros would have liked to recruit more youth to participate in multiple group discussions merely time constraints and the fourth dimension of year (it was summer when many youth were unavailable) limited the depth and scope of our procedure. In the future, we would also like to consult with practitioners/researchers facilitating and studying arts-based MBIs. We would have to carry this consultation using an on-line video/sound platform given our physical location in a smaller city far from larger urban centres, and the lack of similarly engaged professionals in our community. In conclusion, we note that the attention paid to testing arts-based MBIs has not been robust. Given the known benefits of arts-based methods for children and youth, we believe that more focus should be paid to these practices and how mindfulness-based concepts and skills can be taught using these methods. In this manner, more youth may accept the chance to benefit from participating in MBIs.

References

-

Alsubaie, M., Abbott, R., Dunn, B., Dickens, C., Frieda Keil, T., Henley, W., et al. (2017). Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological weather condition: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 74–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.008.

-

Archibald, L., & Dewar, J. (2010). Creative arts, civilization, and healing: Building an show base of operations. Pimatisiwin, eight(iii), 1–25.

-

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Periodical of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

-

Atkinson, Chiliad. J., & Wade, T. D. (2015). Mindfulness-based prevention for eating disorders: A school-based cluster randomized controlled report: Mindfulness-based eating disorder prevention. International Periodical of Eating Disorders, 48, 1024–1037. https://doi.org/x.1002/swallow.22416.

-

Bajaj, B., & Pande, Northward. (2016). Mediating function of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 63–67. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005.

-

Borquist-Conlon, D., Maynard, B., Esposito Brendel, K., & Farina, A. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for youth with feet: A systematic review and meta-assay. Research on Social Work Do, 29(2), one–11. https://doi.org/x.1177/1049731516684961.

-

Burckhardt, R., Manicavasagar, Five., Batterham, P., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Shand, F. (2017). Acceptance and delivery therapy universal prevention program for adolescents: A feasibility study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 11, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0164-five.

-

Carey, Fifty. (Ed.). (2006). Expressive and creative arts methods for trauma survivors. London, Great britain: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005.

-

Chiesa, A., Fazia, T., Bernardinelli, L., & Morandi, G. (2017). Citation patterns and trends of systematic reviews about mindfulness. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 28, 26–37. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.ctcp.2017.04.006.

-

Coholic, D. (2011). Exploring the feasibility and benefits of arts-based mindfulness-based practices with immature people in need: Aiming to improve aspects of self-sensation and resilience. Child and Youth Intendance Forum, twoscore, 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9139-x.

-

Coholic, D., & Eys, M. (2016). Benefits of an arts-based mindfulness grouping intervention for vulnerable children. Child & Boyish Social Work Journal, 33, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0431-3.

-

Coholic, D., Eys, K., & Lougheed, Due south. (2012). Investigating the effectiveness of an arts-based and mindfulness-based grouping program for the improvement of resilience in children in demand. Journal of Child and Family unit Studies, 21, 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9544-2.

-

Coholic, D., Lougheed, S., & Cadell, South. (2009a). Exploring the helpfulness of arts-based methods with children living in foster care. Traumatology, 15, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765609341590.

-

Coholic, D., Lougheed, Due south., & LeBreton, J. (2009b). The helpfulness of holistic arts-based group work with children living in foster care. Social Work with Groups, 32, 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609510802290966.

-

Coholic, D., Schinke, R., Oghene, O., Dano, K., Jago, K., McAlister, H., et al. (2019). Arts-based interventions for youth with mental wellness challenges. Periodical of Social Work. https://doi.org/ten.1177/1468017319828864.

-

Davis, M., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 1386–1400. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010.

-

Diaz, Due north., Liehr, P., Curnan, L., Brown, J. 50. A., & Wall, K. (2012). Playing games: Listening to the voices of children to tailor a mindfulness intervention. Children, Youth and Environments, 22, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.22.two.0273.

-

Fjorback, L., Arendt, M., Ornbol, East., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cerebral therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scand., 124, 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x.

-

Gordon, J. S., Staples, J. Grand., Blyta, A., Bytyqi, M., & Wilson, A. T. (2008). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in postwar Kosovar adolescents using listen-torso skills groups: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 1469–1476. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n0915.

-

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Wellness Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108. https://doi.org/ten.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

-

Greenberg, M. T. (2006). Promoting resilience in children and youth. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1376.01.

-

Harnett, P. H., & Dawe, South. (2012). Review: The contribution of mindfulness-based therapies for children and families and proposed conceptual integration. Kid and Boyish Mental Health, 17, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00643.x.

-

Haydicky, J., Wiener, J., Badali, P., Milligan, K., & Ducharme, J. (2012). Evaluation of a mindfulness-based intervention for adolescents with learning disabilities and co-occurring ADHD and anxiety. Mindfulness, 3, 151–164. https://doi.org/x.1007/s12671-012-0089-2.

-

Hayes, S., Strosahl, Yard., & Wilson, K. (1999). Credence and delivery therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford.

-

Himelstein, S., Hastings, A., Shapiro, South., & Heery, M. (2012). A qualitative investigation of the experience of a mindulness-based intervention with incarcerated adolescents. Kid and Adolescent Mental Wellness, 17, 231–237. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00647.ten.

-

Horesh, D., & Gordon, I. (2018). Mindfulness-based therapy for traumatized adolescents: An underutilized, understudied intervention. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 23, 627–638. https://doi.org/ten.1080/15325024.2018.1438047.

-

Jee, S. H., Couderc, J., Swanson, D., Gallegos, A., Hilliard, C., Blumkin, A., … Heinert, South. (2015). A pilot randomized trial teaching mindfulness-based stress reduction to traumatized youth in foster care. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 21, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.06.007

-

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your trunk and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Delta.

-

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practise, 10, 144–156. https://doi.org/ten.1093/clipsy.bpg016.

-

Kelly, B. L., & Doherty, L. (2017). A historical overview of art and music-based activities in social work with groups: Nondeliberative exercise and engaging young people's strengths. Social Piece of work with Groups, 40, 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2015.1091700.

-

Klassen, S. (2017). Free to be: Developing a mindfulness-based eating disorder prevention programme for preteens. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 3, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2017.1294918.

-

Klatt, M., Buckworth, J., & Malarkey, W. (2009). Furnishings of low-dose mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR-ld) on working adults. Health Educational activity & Behavior, 36, 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198108317627.

-

Klatt, M., Harpster, Yard., Browne, E., White, Due south., & Case-Smith, J. (2013). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes for move-into-learning: An arts-based mindfulness classroom intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology, viii, 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.779011.

-

Lagor, A., Williams, D. J., Lerner, J., & McClure, K. (2013). Lessons learned from a mindfulness-based intervention with chronically ill youth. Clinical Practise in Pediatric Psychology, one, 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000015.

-

Lang, Due north. (2016). Nondeliberative forms of practice in social work: Artful, actional, analogic. Social Work with Groups, 39, 97–117. https://doi.org/ten.1080/01609513.2015.1047701.

-

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, One thousand. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, i–9. https://doi.org/ten.11186/1748-5908-5-69.

-

Livheim, F., Hayes, L., Ghaderi, A., Magnusdottir, T., Hogfeldt, A., Rowse, J., … Tengstrom, A. (2015). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for adolescent mental health: Swedish and Australian airplane pilot outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1016–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9912-nine.

-

Lougheed, S., & Coholic, D. (2016). Arts-based mindfulness group work with youth aging out of foster care. Social Work with Groups, 41, 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2016.1258626.

-

Malchiodi, C. (2007). The fine art therapy sourcebook (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

-

Meagher, R., Chessor, D., & Fogliati, Five. (2018). Treatment of pathological worry in children with acceptance-based behavioral therapy and a multisensory learning aide: A pilot study: Credence-based anxiety handling for children. Australian Psychologist, 53, 134–143. https://doi.org/x.1111/ap.12288.

-

Milligan, K., Badali, P., & Spiroiu, F. (2015). Using integra mindfulness martial arts to address self-regulation challenges in youth with learning disabilities: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9868-1.

-

Milligan, Thou., Irwin, A., Wolfe-Miscio, Chiliad., Hamilton, 50., Mintz, L., Cox, M., …Phillips, M., (2016) Mindfulness enhances utilise of secondary control strategies in high school students at chance for mental health challenges. Mindfulness, vii, 219–227 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0466-8

-

Perry-Parrish, C., Copeland-Linder, N., Webb, Fifty., Shields, A. H., & Sibinga, E. (2016). Improving cocky-regulation in adolescents: Current evidence for the office of mindfulness-based cerebral therapy. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 7, 101–108. https://doi.org/x.2147/AHMT.S65820.

-

Pham, M., Rajic, A., Greig, J., Sargeant, J., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, v, 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123.

-

Dial, South. (2002). Research with children: The same or dissimilar from enquiry with adults? Childhood, 9, 321–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568202009003005.

-

Ruskin, D., Gagnon, Thousand., Kohut, S., Stinson, J., & Walker, K. (2017). A mindfulness plan adapted for adolescents with chronic pain: Feasibility, acceptability, and initial outcomes. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 33, 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000490.

-

Segal, Z., Williams, J., & Teasdale, J. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new arroyo to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press.

-

Simpson, S., Mercer, South., Simpson, R., Lawrence, M., & Wyke, S. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for young offenders: A scoping review. Mindfulness, 9, 1330–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0892-5.

-

Sinding, C., Warren, R., & Paton, C. (2014). Social work and the arts: Images at the intersection. Qualitative Social Work, 13, 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325012464384.

-

Tan, 50., & Martin, G. (2013). Taming the adolescent heed: Preliminary report of a mindfulness-based psychological intervention for adolescents with clinical heterogeneous mental health diagnoses. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, eighteen, 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104512455182.

-

Tan, L., & Martin, G. (2015). Taming the adolescent mind: A randomised controlled trial examining clinical efficacy of an adolescent mindfulness-based group plan. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20, 49–55. https://doi.org/ten.1111/camh.12057.

-

Tharaldsen, K. (2012). Mindful coping for adolescents: Beneficial or confusing. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 5, 105–124. https://doi.org/ten.1080/1754730X.2012.691814.

-

Thompson, Yard., & Gauntlett-Gilbert, J. (2008). Mindfulness with children and adolescents: Effective clinical awarding. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry, thirteen, 396–408. https://doi.org/ten.1177/1359104508090603.

-

Van Vliet, K. J., Foskett, A., Williams, J., Singhal, A., Dolcos, F., & Vohra, Southward. (2017). Affect of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program from the perspective of adolescents with serious mental health concerns. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 22, 16–22. https://doi.org/ten.1111/camh.12170.

-

Vollestad, J., Birkeland Nielsen, Thousand., & Hostmark Nielsen, Yard. (2012). Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51, 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02024.10.

-

Wall, R. B. (2005). Tai chi and mindfulness-based stress reduction in a Boston public center school. Journal of Pediatric Wellness Care, 19, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.02.006.

-

Waltman, S., Hetrick, H., & Tasker, T. (2012). Designing, implementing, and evaluating a group therapy for underserved populations. Residential Handling for Children & Youth, 29, 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571x.2012.725374.

-

Yook, Y. S., Kang, S. J., & Park, I. (2017). Effects of concrete action intervention combining a new sport and mindfulness yoga on psychological characteristics in adolescents. International Journal of Sport and Do Psychology, fifteen, 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2015.1069878.

-

Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, South., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603.

Acknowledgement

Nosotros acknowledge the assistance of Mr. Ashley Thomson, Librarian at Laurentian University. The research described in this paper was supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Writer information

Affiliations

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Disharmonize of interest

The authors declare that they accept no conflict of involvement.

Boosted information

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long equally yous give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the commodity's Artistic Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is non permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted employ, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coholic, D., Schwabe, N. & Lander, K. A Scoping Review of Arts-Based Mindfulness Interventions for Children and Youth. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 37, 511–526 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00657-v

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00657-v

Keywords

- Mindfulness

- Arts-based

- Youth

- Scoping review

montgomeryslosicessir.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10560-020-00657-5

0 Response to "Literature Review Mindfulness Interventions With Youth Learning Disabilities"

Post a Comment